Article | July 31, 2025

Clean Metadata, Credible Insights: The Critical Role of Diligent Metadata Preprocessing

Authored by Cameron Lamoureux, PhD, Senior Data Scientist, Sapient

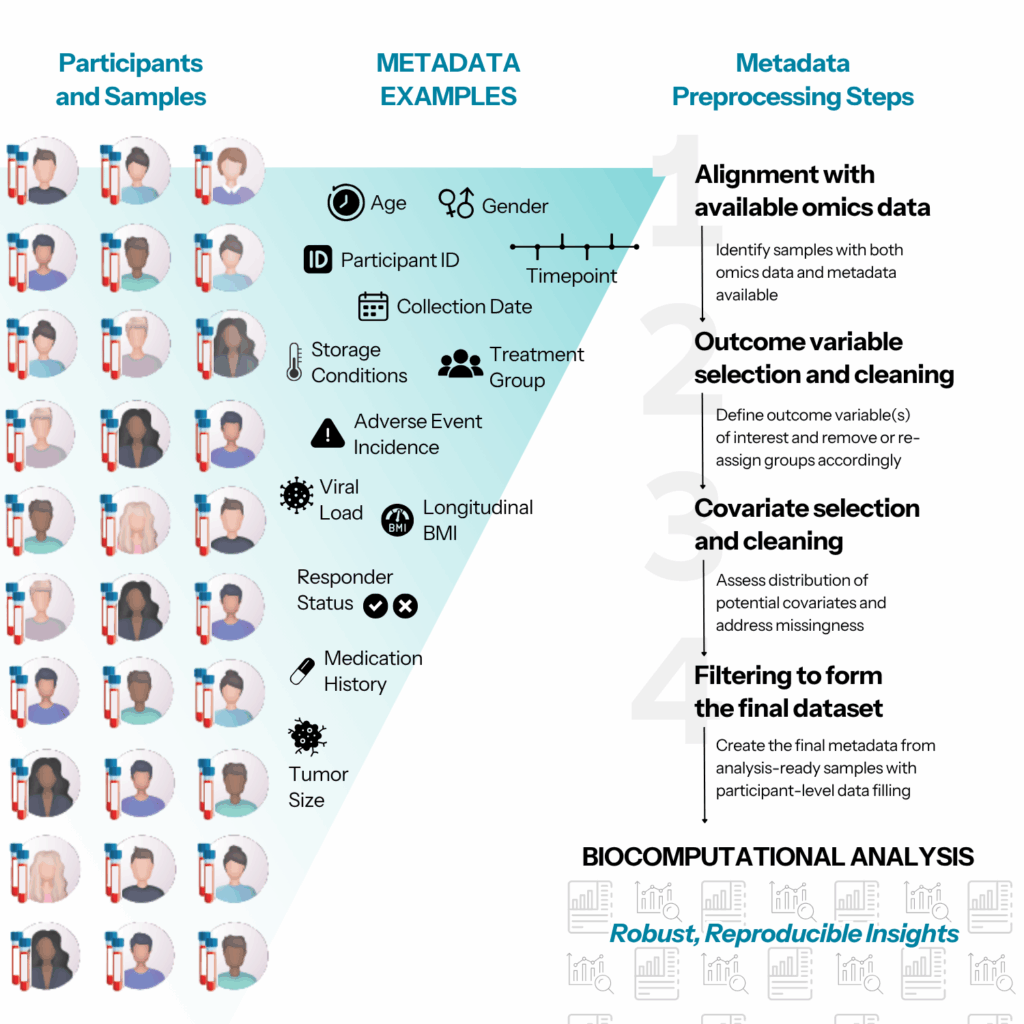

In human studies, metadata is arguably the most important input for any biocomputational analysis. Metadata is separate from the omics measures generated for a study and provides critical context about how samples in that study were collected, and from whom. It is essential that this metadata, which stems from diverse sources, is consistently harmonized and accurately utilized with respect to the overall study goals, ensuring insights that are derived from the data are both meaningful and reproducible. Therefore, careful metadata preprocessing is an essential foundational step that requires extreme diligence and thoughtfulness to avoid invalidating downstream data analysis.

Metadata, broadly speaking, refers to any available information about the participants and/or samples that are included in a given study. At the participant level, metadata may include common demographic information such as age, gender, and ethnicity. Critical sample-level information often includes details about sample processing such as coagulant used, the collection timepoint (for longitudinal sampling), and of course the corresponding participant ID.

However, the most important component of metadata includes the outcome variables defined in the study. Outcomes may be categorical, e.g.: treatment group assignment, incidence of adverse outcome, or responder/non-responder status. Outcomes may also be continuous, or even longitudinal, e.g.: weight measurement over time, tumor size reduction over time, or circulating viral load. The nature of the outcome variables will directly impact the design of the statistical analysis plan used to identify omics measurements associated with or predictive of the outcome of interest.

Without clear, standardized, consistent biological metadata analysis, generating actionable biological insights from large-scale omics datasets from human studies is impossible. Missing or incorrectly formatted metadata can cause analytical errors or bias, leading to misinterpretation or lack of reproducibility in results. Therefore, we aim here to discuss a set of steps, checks, and best practices for metadata preprocessing to ensure robust, consistent, analysis-ready metadata.

Metadata preprocessing consists of the following key steps: (1) alignment with available omics data; (2) outcome variable selection and cleaning; (3) covariate selection and cleaning; and (4) filtering to form the final dataset.

(1) Alignment with available omics data

Naturally, biocomputational analysis relies on samples for which both omics data and metadata are available. However, this alignment is not always perfect. In other words, certain samples may have omics data available but have no associated metadata, or vice versa. Identifying aligned samples which have both data types is a useful first step, as it isn’t sensible to perform subsequent metadata preprocessing work on samples that cannot be fully analyzed. Additionally, this step can help ensure that the sample ID mapping between the omics data and the metadata is consistent. Simple typographical errors or other issues that prevent perfect alignment can be identified and rectified early in the process.

(2) Outcome variable selection and cleaning

Identifying the outcome variable(s) of interest is the next key step. It is important to carefully weigh considerations such as, is the outcome at the sample or the participant level? Is it categorical or continuous? How many groups if categorical? Is it longitudinal/time-based? Are there any outcome groups that should be removed as they are not relevant to the study goals, or the number of participants or samples in the group is too small to have any statistical power? Should some of the outcome groups be re-assigned? For example, this may involve re-assigning complete response, partial response, stable progression all into responders; or re-assigning severity levels one to six into mild, moderate, and severe.

As discussed previously, selection bears significantly on the overall design of a statistical analysis plan, and these questions can help guide the selection and transformation of an appropriate outcome. It is also critical to assess the distribution of the outcome. Class imbalance (for categorical variables) and outliers (for continuous variables) are potential confounding factors that need to be accounted for in the downstream analyses and should be recognized up front. Finally, missingness in an outcome variable is almost always cause for exclusion for analysis. However, it is critical to wait until step (4) for explicit removal – at this stage, just noting the samples with missing outcomes is sufficient.

(3) Covariate selection and cleaning

Covariate selection depends on two main factors: study design and missingness. Key covariates to always consider controlling for are basic demographic variables such as age and gender. For longitudinal data, controlling for repeated measures from the same participants, or for the timepoint, is often advisable. Moreover, missingness is common for metadata in human studies and may be handled in different ways depending on a few key factors. Imputation is an acceptable choice for covariates that have relatively low missingness percentages (usually no more than 10-15%).

While complicated imputation methodologies that aim to consider relationships between metadata variables do exist, these are often computationally expensive and introduce potentially unwanted or unverified assumptions into the analysis. Thus, when possible, simpler imputation methods, such as median or mode imputation, can still be effective. Assessing the distributions of potential covariates at this stage is also critical to identify if additional normalizations – such as log transformation for right-skewed continuous covariates – is necessary.

Final covariate selection involves balancing these different considerations. If the number of samples in the study is already small, it may not be feasible to further reduce sample size in order to include a covariate with significant missingness. On the other hand, if many samples are available, restricting the study to those samples that also have non-missing values for key covariates may be sensible. One final consideration when assessing covariates is to use all available metadata to identify covariates for a given sample. In some cases, metadata at the sample level can include participant-level covariates that are “missing” in a subset of the participant’s samples, but present in other samples from the same participant. If these covariates are “static” – e.g. medical history that was only assessed at an initial screening – this information could be lost if that sample were prematurely dropped. Thus, as mentioned in step (2), it is prudent at this step to note the samples with missing covariates, but not necessarily to drop them.

(4) Filtering to form the final dataset

Now that analysis-ready samples have been identified, the final step involves creating the final metadata that reflects the final samples that will be used in subsequent exploration and analysis steps. Samples with missing outcomes or missing covariates should be handled first by filling in participant-level data that may only be present in a subset of the samples that belong to the participant. After this participant-level data-filling step, samples with missing outcomes may be dropped. Final summaries of sample counts by group, and final covariate distributions, may be assessed. The resulting preprocessed metadata is ready to proceed to exploratory and statistical data analysis.

Complete, well-curated metadata is integral to effective biocomputational analysis in human studies, providing the necessary biological and technical context needed to accurately interpret omics data generated for these studies. Metadata preprocessing is critical to verify, harmonize, and align diverse metadata associated with both samples and participants, and requires extreme diligence and thoughtfulness to ensure the integrity of downstream analyses. By applying these best practices for metadata preprocessing, we can be confident that biocomputational outputs are both valid and reproducible.